World Press Photo Feature Artist: Adam Ferguson

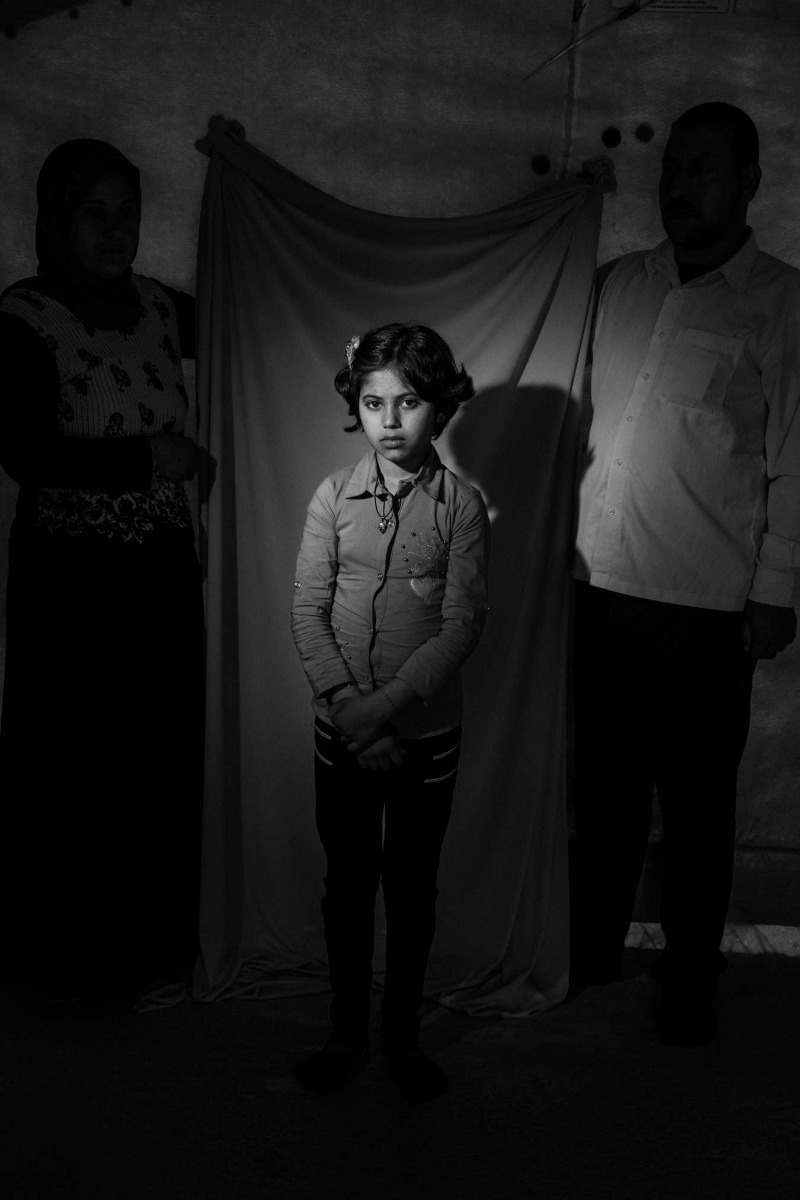

At very young ages, the children in Adam Ferguson's series The Haunted have already faced unimaginable challenges: kidnappings, slavery, the loss of siblings and parents.

His portraits for The New York Times Magazine of displaced Yazidi people and other minorities who have suffered human rights violations won First Prize in the 2020 World Press Photo Contest within Portraits, Stories.

They are currently on display at the State Library of New South Wales as part of its touring exhibition, until October 18. He spoke to Sunroom about the experience of making this powerful work.

Rezan (11), who was kidnapped by IS in 2014 and freed in early 2019, at the Khanke IDP Camp in Dohuk, Iraqi Kurdistan. © Adam Ferguson for The New York Times Magazine.

STATEMENT

As the Islamic State group (IS) retreated from territory around Mosul in northern Iraq, thousands of former IS prisoners were liberated, many in severe states of trauma.

The photographer took posed portraits of displaced Yazidi people and other minorities who had suffered human rights violations perpetrated by IS, in camps for displaced people in northern Iraq.

The Yazidi religion is monotheistic and can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamian and Abrahamic roots. Due to their unique beliefs, the Yazidi people were seen by the Sunnis of IS as “devil worshippers”.

When IS occupied ancestral Yazidi lands in northern Iraq in 2014, IS fighters massacred around 5,000 Yazidi men. Women and girls were abducted and forced into sexual slavery, and boys forced to train as child soldiers.

Some 500,000 Yazidis were displaced. Many now live in refugee camps in Iraqi Kurdistan and Nineveh Governorate in Iraq. Jan Kizilhan, a psychologist working in one such camp at a centre for people who survived the atrocities, points to the effects of this severe personal and cultural trauma. These include feelings of helplessness and powerlessness, tension, and a variety of physical illnesses.

Kristina (12) was kidnapped by IS in 2014 and freed in April 2019, after IS were driven from Baghouz in Syria. She cried when she left the IS family that was keeping her captive. Kristina was taken to the Sharia IDP Camp in Dohuk, Iraqi Kurdistan. © Adam Ferguson for The New York Times Magazine.

INTERVIEW

You'd covered the Yazidi exodus from ISIS back in 2014. At what point had you entered the unfolding story then, and did that experience inform the way you worked on this follow up?

I was already working in Iraq when ISIS swept through the north of the country taking Sinjar, a predominantly Yazidi district on the Syrian border. On August 11, 2014, I photographed tens of thousands of Yazidi streaming across the Iraqi border after fleeing their homes.

Many had their children kidnapped and husbands executed by ISIS. After clearing the Tigris River, most of the women collapsed in exhaustion with tears and grief.

On Aug 12, I flew on an Iraqi military rescue helicopter into the Sinjar mountains where many Yazidi remained trapped. The helicopter crashed and the pilot and four of the Yazidi died. This experience and my own trauma no doubt informed the work I made in 2019.

Delivan (10) was held by IS from 2014 until March 2019. His older brother died during a bomb attack while also captive, and their father is still missing. Delivan lives with his mother in Kabrato Camp 1 in Dohuk, Iraqi Kurdistan. He is violent and often beats her and his brothers. © Adam Ferguson for The New York Times Magazine.

I understand you were now returning to the story five years later, with so many people still displaced and some of the abducted by ISIS beginning to be reunited after its fall. But they were not straight forward reunions with easy closure. What were your initial thoughts on how to approach the largely invisible and interior story of trauma visually?

It was my intention to create a set of portraits that convey the immense emotional toll of the war in Iraq.

It was important to make images that asked an audience to feel the psychological trauma that exists for many of the civilians who endured those recent years.

Most of the families I met were extremely open and welcoming. The Yazidi population in particular had suffered some of the most severe persecution and I believe they wanted to share their stories, they wanted to be heard. It was my intention to make photographs that honoured each subject with a sense of dignity, although I also attempted to make portraits that felt fraught and sad, for their experiences contained those emotions on a very raw level.

How long did you have to make this work on assignment?

I worked on this assignment for about 10 days.

Jitan (14), pictured in Khanke Village, Dohuk, Iraqi Kurdistan, was kidnapped in 2014 and now speaks Arabic better than his native Kurdish. Several members of his family are still missing. © Adam Ferguson for The New York Times Magazine.

Why was it important to you to put a human face to this issue and their experience?

I believe this story is incredibly important to hear and engage with.

The rise of ISIS can be partly attributed to the foreign intervention in Iraq, and now that intervention has been reduced, we cannot forget about the civilians most impacted by the larger geopolitical decisions and policies that have been supported by the US, European and Australian governments.

Do you have a sense of what was next for the people you photographed? Were they planning to return home or was that no longer an option?

The families I met had a lot of healing ahead of them. Some of the children had been kidnapped at four and reunited with their parents at eight years of age.

After spending half their lives with ISIS families, many of the children now spoke Arabic better than Kurdish. All this created a very complex assimilation when returning to their families. Some of the children missed their ISIS captors.

Hediya (9) spent five years enslaved by IS. Her sister Kristina was also held by IS for five years, but the girls were reunited with their parents in April 2019, after the liberation of Baghuz. © Adam Ferguson for The New York Times Magazine.

What does it mean to you to have this work recognised by World Press Photo?

The World Press Photo is exhibited all over the world and this gives the story I made a new life and larger audience - this is really the most important part of being awarded.

Adam Ferguson website | Instagram

World Press Photo 2020 @ the SLNSW

Noora Ali Abbas (60) sits with her grandson Harreth (6) in their tent in Salamiyah IDP Camp 2, Nineveh, Iraq. Noora says Harreth’s father was taken by IS in 2015, but Harreth is stateless and unable to get an Iraqi government ID because the authorities believe his father was an IS fighter. Noora suffers from depression and anxiety and doesn’t like to let Harreth out of her sight.